Although I did not fully agree with its conclusions, this article for CityLab was an illuminating history of mass transit in America. I heartily encourage people to read the entire thing; they will recognize phases through which their own cities have passed, and the effects of which they still experience. Features of the recent past can be so familiar that this very familiarity renders the forces shaping those features invisible without a narrative to point them out. This article did so. But let’s discuss my disagreement:

Its author contends that disinvestment in mass transit was the primary factor in hastening its demise during the era of the private automobile.

He’s not wrong, but neither is he entirely right. In particular, he de-emphasizes two important factors that I believe bear more weight:

- When two infrastructures compete for the same consumers in a winner-takes-all environment, only one will prevail.

- Mass transit must co-evolve with dense development. Without one, the other cannot persist.

Mass transit flourished as long as vehicle costs were high and lack of diffuse infrastructure focused commuter dollars on those means of transit. But the revolution initiated by Henry Ford made the private automobile attainable, while public infrastructure investments began swiftly to favor road construction over rail. Here a decision had to be made: roads and rails overlapped in services offered. We only needed one or the other – especially since the benefits of either are best achieved by wholly eliminating the other (we save money by eliminating a car, for example). As with any choice of public utility, disproportionate advantage accumulates to whichever provider begins to achieve ubiquitous coverage. We’ve seen this more recently with cell phone networks; earlier it was power utilities; right now companies like Google and Amazon are fighting for control of consumers’ data.

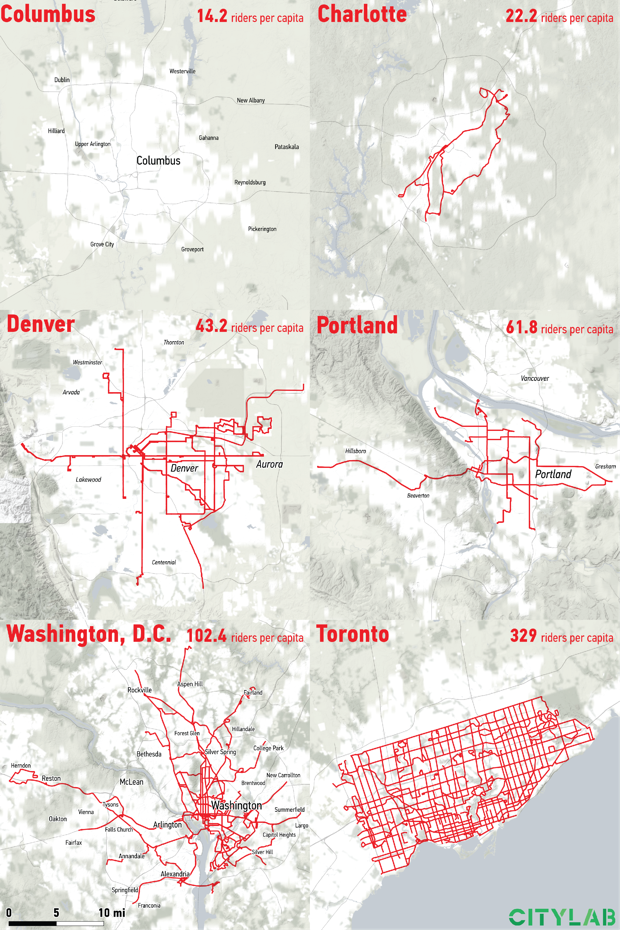

We were forced to make a choice regarding how we wanted to live; it was only a question of which and how swiftly the transition was made. Because public dollars increasingly landed on the side of road-building, private automobiles and paved roads won swiftly and decisively over mass transit infrastructure. There was little time even for mass transit to rebound and define itself a niche, though Mr. English’s history illustrates those rearguard actions it was able to imperfectly fight. Only older cities which had already grown up (densely) around mass transit were able – by and large – to maintain demand for that transit. And that is because they were already so dense and so big that it was inconvenient to drive. In other words, a defensible market niche existed in those places. This is another major reason why Europe never really followed America in building around the private automobile; their cities had already developed and the pattern was set. Amnesiac America had very little such precedent. So let us discuss density:

Unless service is seamless, mode transfers are a pain. When I lived in NYC, if I could have chosen between an hour-long drive and my hour-long walking-to-bus-to-ferry-to-walking commute, I probably would have chosen the drive. This because mode changes entail decisions, and decisions extract scarce mental energy. Mass transit service – especially when it involves changes of mode – cannot be seamless where population (therefore ridership) density is so low that it is uneconomical to run frequently everywhere. So buses (and certainly rail) could not affordably follow to diffusely-developed hinterlands where newly-paved roads led. They always required greater density to justify the investment. And low land prices available further out ensured that none of this new landscape ever achieved density required to justify mass transit. (I am indebted to Bill Cronon’s book Nature’s Metropolis for this insight. Highly recommended.) Starved of ‘oxygen’ in this diffuse environment, they could not compete – especially while federal dollars continually pumped vigor into road construction. It was hardly a fair fight – especially on this uneven playing field.

Regarding public infrastructure investment: “a little bit of all of the above” is not a viable infrastructure policy. Extremely low density and mass transit cannot coexist in the same place, and wishful thinking with scarce public dollars will not make it so. Citizens and policymakers should think hard about the existing assets of their cities as they consider how best to connect this varied urban fabric. Transit and form-based zoning should work hand-in-hand to intensify density where it was already inclined that way, and funding should concentrate on making these core areas a success. As they succeed – and the advantages of urban living make themselves known again to a marketplace deprived of such options – we should see residents vote with their feet and their dollars. Key indicators: low vacancies in urban apartments; high rent-per-square-foot numbers (even though far lower rents are available in less dense locations); spontaneous local retail springing up and flourishing; hipsters ditching their cars – and bigger metros – because these aren’t needed anymore…. Watch for the signs and water what grows!

One thought on “Jonathan English (for CityLab) on How America Killed Transit”